Posted by Anne M on Wednesday, Feb 8, 2017

Selina Peake doesn’t have a lot of options when her father, a professional gambler, is killed by a stray bullet in a Chicago gambling parlor. This being the turn-of-the-century, Selina, armed only with an education and enough money for two dresses (one in burgundy cashmere), decides to become a school teacher and takes a position in the Dutch farming community of High Prairie just outside of the city. Let’s just say she isn’t used to the rural culture. But it is her newness and her novel ideas (she is very well read on farming techniques) that catch the eye of Pervus DeJong and they marry.

But Edna Ferber’s So Big is not the story of Selina’s romance. This is no marriage plot. It is the story of her drive to make her farm profitable after Pervus’s death and the consequences of her success on her relationship with her son, Dirk. How can a woman, who can’t even vote, build a successful vegetable business when all the farmers around her are barely making ends meet? What are her hopes and dreams for her son? What will he make of his life?

This is the first book I have read by Edna Ferber and I loved it. I appreciated Selina’s resolve and her stubbornness, but I also admire her love of learning and curiosity. Although this is definitely a story of American exceptionalism —one of those “pick-yourself-up-from-your—bootstraps” tales—it doesn’t feel like one. So Big explores conflicting values, generational clashes, and living during an era of phenomenal social change. Ferber’s writing is clear and fresh, transcending many of the novels of the early twentieth century. If you enjoy Willa Cather, put So Big on your reading list.

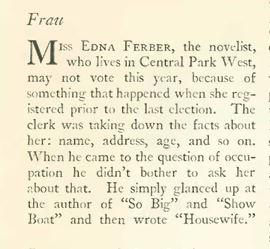

I also have to share this piece from The New Yorker’s “The Talk of the Town” from the September 22, 1928 issue:

If you are a fan of Karina Longworth's "You Must Remember This" podcast, this is the book for you. Longworth sorta, kinda started this book through her podcast--some of her earlier episodes make up the chapters describing Hughes' time in the 1930's. But this is a much deeper dive. So much so, that I think I now know too much about Howard Hughes' love life. -Anne M